Under the Sun of Lubumbashi: Between Albinism, Resilience, and Climate Challenges

SIMON’S JOURNEY AS A PERSON WITH ALBINISM

Listen to the audio version of Simon’s story (In French)

My name is Simon Pierre Kalenga Kalonji, I am the child of Upper Katanga, in the Democratic Republic of Congo. I grew up in Lubumbashi, a city rich in mineral resources, a land coveted for its treasures, but to me, it is much more than that. It is a special land, a place where the rivers bring a temporary freshness in the face of an increasingly merciless sun.

Growing up here, as a person with albinism, has never been easy. I still remember my first day of school. At five years old, I proudly walked forward, backpack on, ready to discover this new world. But as soon as I entered the classroom, the children ran away, frightened by my difference. That day, I understood that my albinism separated me from others, that my fair skin and almost white hair created a barrier I could not control.

I spent a long time questioning myself in front of the mirror:

Why was I born like this? Why isn’t my skin like everyone else?

These questions haunted me until I learned to accept my reflection, and more so, to embrace my difference with pride.

But I didn’t know that the door to even greater challenges was about to open before me.

Today, I face a far more insidious threat than the discrimination I have experienced: climate change.

The heat, and more worryingly for us, people with albinism, the increase in UV rays, has now become a real enemy.

Nowadays, from September to May, the sun burns with an intensity that my skin can no longer withstand. By 9:30 a.m., I cannot stay outside without feeling the direct effects of climate change on my body. My skin reddens, spots appear, and sometimes I experience deep burns. It is as though the sun, once a mere source of light, has become an unforgiving predator, stalking me and my brothers and sisters with albinism.

The pain of being under the sun is sometimes so intense that I am forced to flee, desperately searching for a life-saving shadow. But fleeing is not an option.

For people with albinism, earning a living, on top of the multiple socio-economic barriers, means facing the direct effects of climate change every day. We are forced to go outside, to work, to fight for a dignified life, to venture out just to survive. Yet, every day spent outdoors is a dangerous gamble.

Prolonged exposure causes the skin to lose its glow, and tumors appear, often fatal. Too many of my brothers and sisters have left this world far too soon, without ever having had the chance to live.

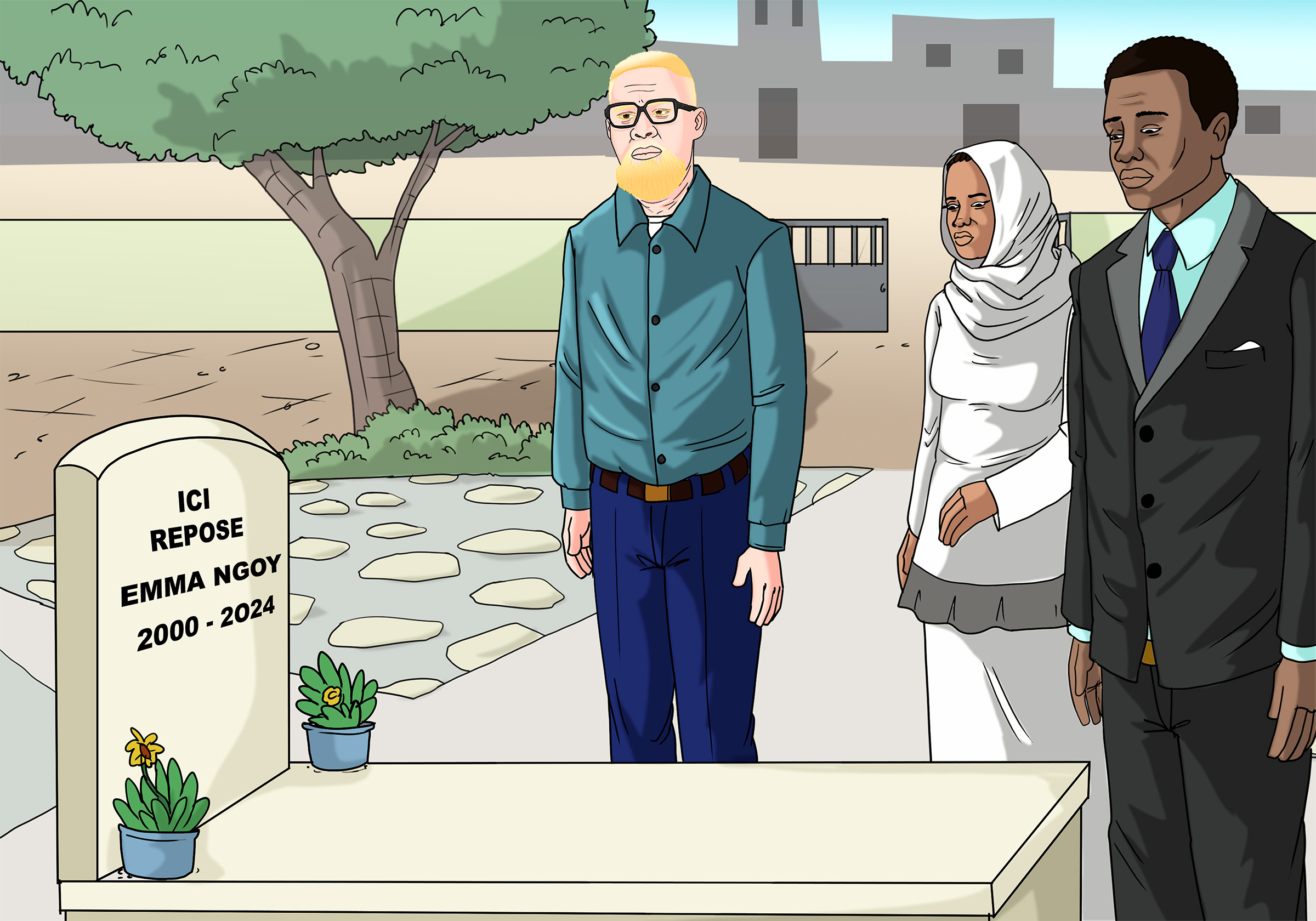

I think of Emma, a young friend with albinism. She was 24 years old, full of ambition.

She had completed her studies and started a business selling slippers to support herself. But gradually, lesions appeared on her skin. When we realized the seriousness of her condition and took her to see a doctor, it was already too late.

She passed away, taken by an illness we know all too well and fear with all our hearts.

Every day, people with albinism face life-threatening risks due to inadequate protection from the sun’s UV rays. In just six months, fifteen people with albinism have died of skin cancer in our city (OBEAC 2021). We lack critical resources, even the most basic one: sunscreen. It’s a luxury many of us cannot afford. The lack of proper treatment means that 90% of people with albinism in Africa do not live beyond the age of 40. This statistic is terrifying, and it is our daily reality (Rao 2018).

Climate change not only affects our physical health but transforms our lives.

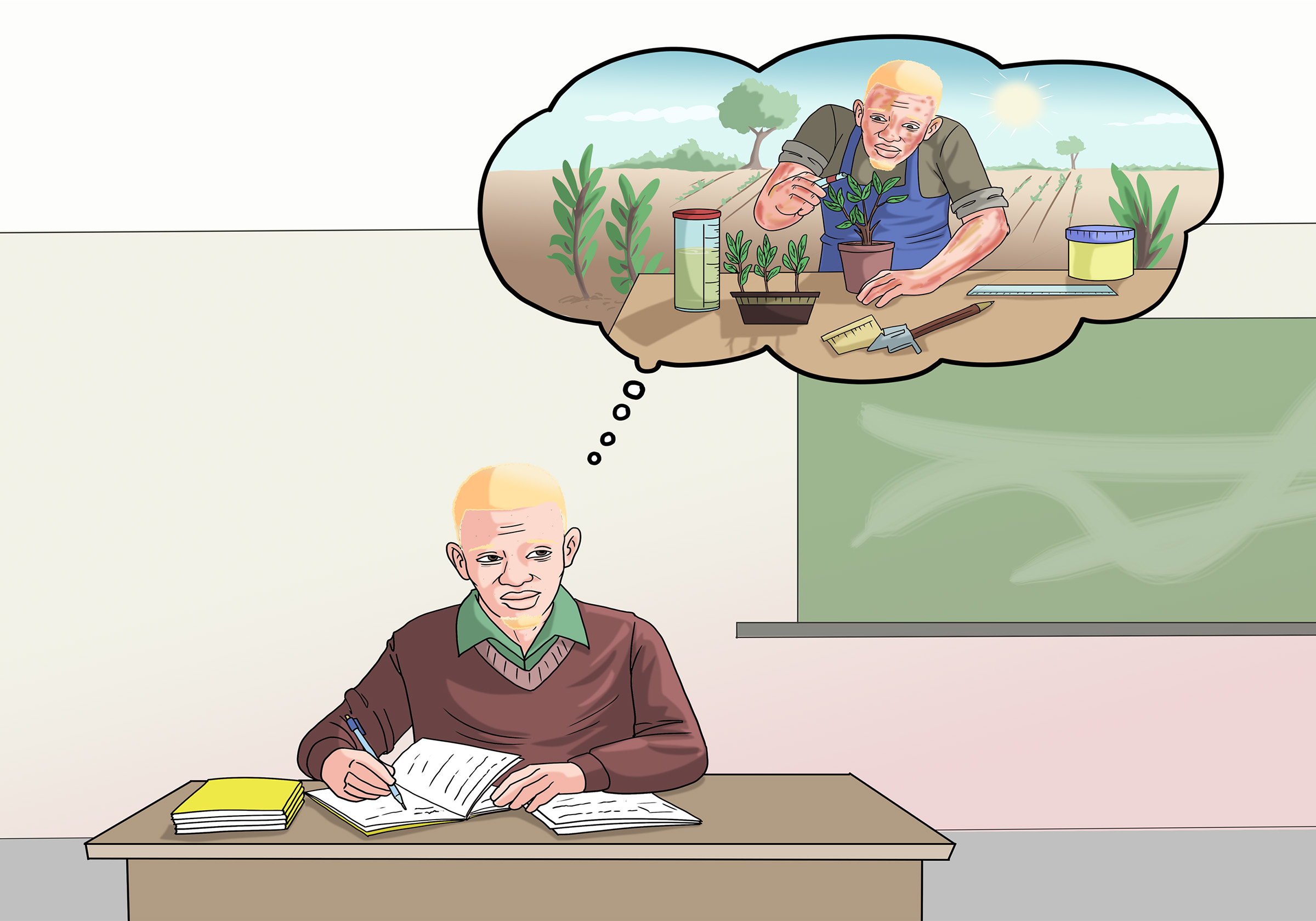

Many of us have had to give up our dreams and passions. Some of my friends who studied agronomy, environmental science, or even business were forced to change paths, unable to work under the sun with albinism. We are pushed towards jobs that allow us to stay indoors, away from the rays, even if it means abandoning our deepest ambitions, and even though this option to work is not available to all of us.

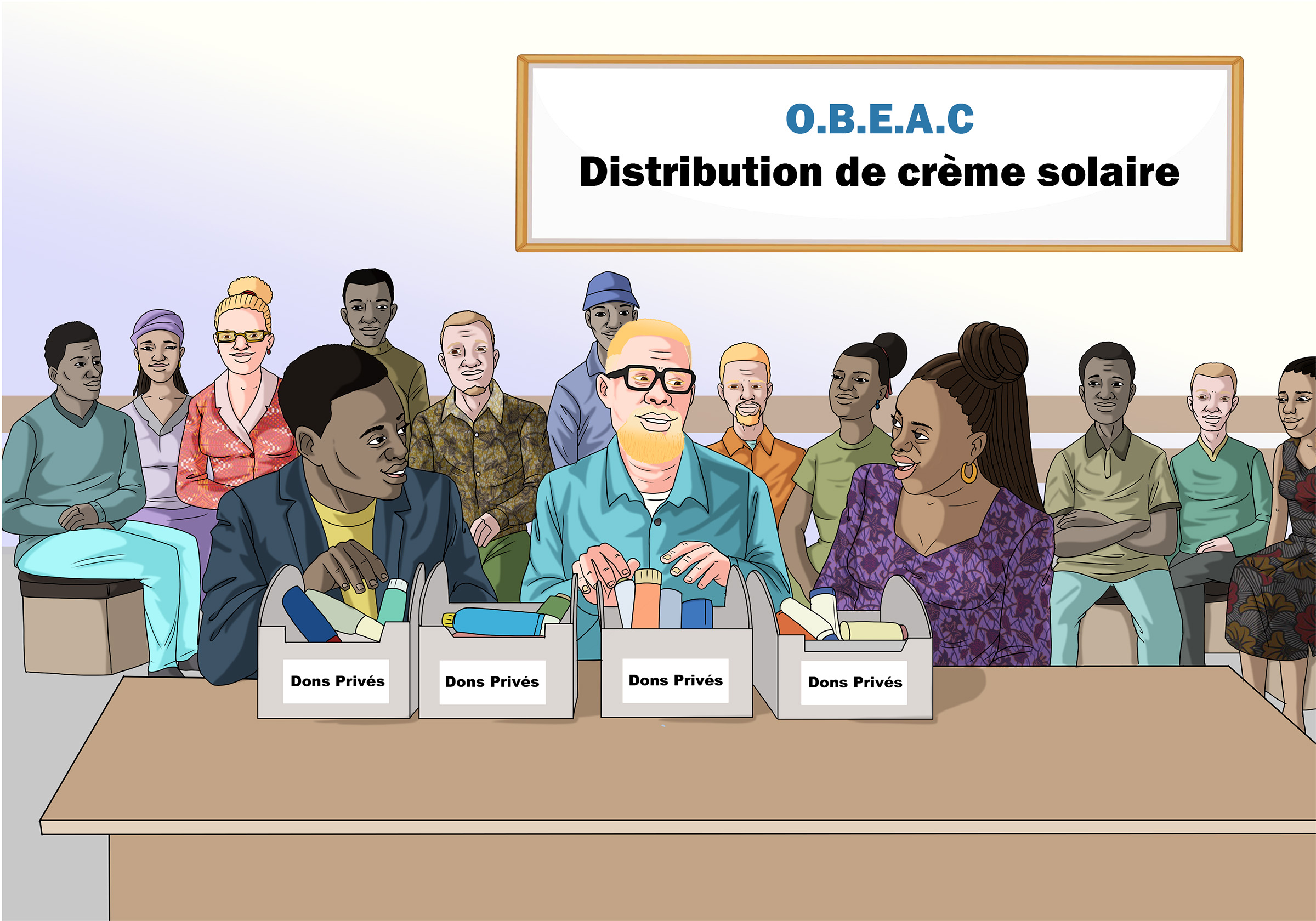

Today, I lead the Organization for the Welfare of People with Albinism in Congo (OBEAC). We are a strong community, united by bonds of solidarity in the face of the challenges we encounter. We educate our brothers and sisters about the dangers of the sun and explain how best to protect themselves: wearing long clothing, hats, and avoiding prolonged exposure. We strive to distribute sunscreen, but our efforts are often insufficient. We appeal to the authorities, hoping that one day they will recognize our situation and take action.

I dream of a future where we are better protected, where sunscreen is accessible to all, where our governments take into account the effects of climate change on people with albinism.

We are among the first victims of global warming, yet we are often the last to be heard.

We need you—decision-makers and social change agents. Grant us access to sun protection, include us in climate justice discussions now and for the future. Together, we can build a world where our differences are not a weakness, but a strength. Together, we can create a future where people with albinism can live fully, without fearing death, whether in the sun or in the shadows.

About Simon Pierre Kalenga

Simon Pierre Kalenga is a human rights advocate from the Democratic Republic of Congo and has albinism. He is the President of the Organization for the Welfare of People with Albinism in Congo (OBEAC), an organization dedicated to protecting and promoting the rights of people with albinism. Simon advocates for greater awareness of albinism and actively fights against the discrimination and marginalization faced by people with albinism.