Politics is one of the most significant spaces to demonstrate the genuine inclusion of human diversity. In the last decade, I have been honored to represent marginalized groups, particularly people with disabilities in the Kenyan Parliament. First as a Member of Parliament (MP) and then later in the Senate. Since day one, I took this position seriously and did all I could to show that I was not a filler or placed there to check the box that the government was being inclusive. This was easy for me because politics comes to me as second nature. Moreover, I strongly desired to serve and make a mark for those I was called to represent.

I remember the first time I went to Parliament. It was the time before I was appointed to serve there. As soon as I stepped in, sat, observed keenly, and listened intently to the debates, I knew that I would fit in. I recognized in them some of the talents that I had been given, including oratory capacity, interpersonal skills, and the zeal to serve.

I am very proud of my accomplishment in parliament.

I could make a very long list, but since I was invited to make this comment by the Africa Albinism Network, I will focus on my accomplishment for people with albinism in Kenya. In my 9 years in the Kenyan Parliament, I have been able to bring the issue of albinism into the national conversation. As the first person of albinism in the Parliament and the Senate. I am the only person with disabilities who has represented people with disabilities in both houses of Kenya. I have laid the foundation for people who look like me. Just months ago, Kenya historically elected a person with albinism, Martin Wanyoyi. Martin dresses how I do. I am so proud of that. I also supported Judge Mumbi Ngugi in her post.

I helped to put in place a robust national budget for PWA with a consequential program with priority areas in health and access to education. This program, serviced through the National Council on Disabilities, provides PWA with free sunscreen and cancer treatment. It has greatly prevented skin cancer and reduced death from the condition.

I sensitized the national youth service on PWA. The other day, I saw a PWA in a serving as a security guard in a parade. To me, this was a consequence. I have witnessed PWA as Kadets and in diverse industries such in administrative services, supermarkets, hospitality, among others. I conceptualized and implemented several editions of Mr. and Mrs. Albinism which often led to employment and created opportunities for PWA. I supported election participation for PWA and provided access to education by tuition for many, and as a result, I know that many more have been served due to the multiplier effect of investment in health, education, and employment.

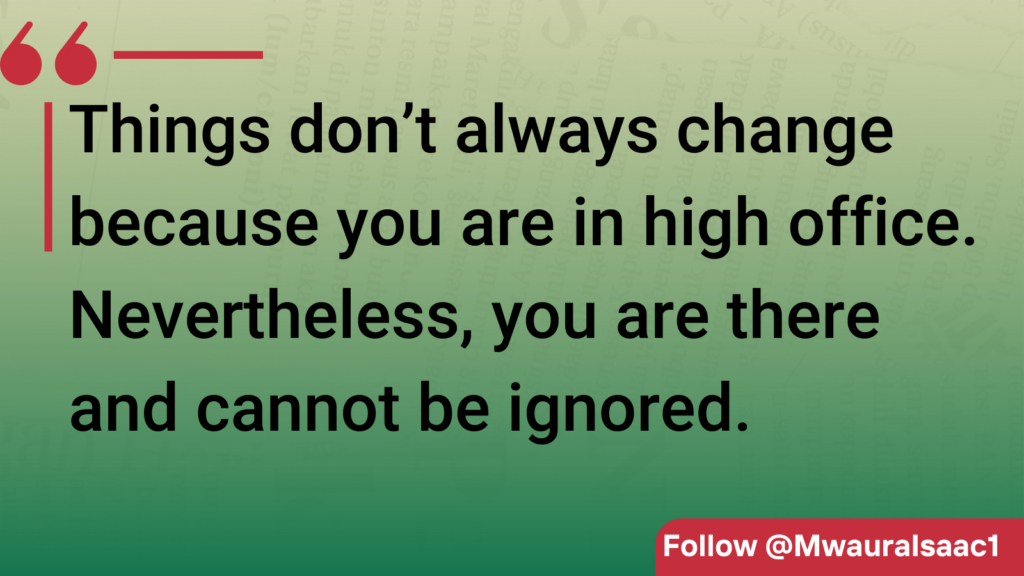

With a keen belief that politics organize society, I pushed to have PWA in key positions. Aside from my parliamentary appointments, I ran twice, albeit unsuccessfully, in Ruiru to be their elected MP. However, that engagement exposed me to how people saw me and the historical effect of my placement in politics. People have told me that they see value in my leadership. A general desire to see me remain in leadership indicates a narrative change. With the right person appointed into office, even though positive discrimination, a society can be more inclusive.

Several PWA have been employed to continue with Kenya’s unique accomplishments on the issue of PWA within the executive. We now know the number of PWA in the country as our national census captured that data for the first time. There is a greater awareness and acceptance of PWA in the country. You don’t feel the stigma like before. I feel more comfortable when I walk around Kenya. Because of all of this, at the continental level, Kenya stands out. I hear in the albinism community of the “Kenya model”, which is a way to refer to all the measures we have taken to make a more inclusive society for PWA. Our model has inspired other countries such as Malawi. Malawi is coming well with an MP with albinism as well as a Human Rights Commissioner with albinism – both are firsts. Malawi must also be commended for taking a relatively strong judicial stance on the cases of attacks against people with albinism.

We are now using all our experience and gains in the past decade to develop our national action plan (NAP) on albinism to mirror the AU (African Union) Plan of Action. It is with pride that I know that all our measures for albinism informed the AU Plan of Action in the first place. However, the NAP is an opportunity to have all the measures that have worked for us in one place while adding relatively new ones to challenge us in the next decade.

The first barrier to implementing NAPs (National Action Plans) – from the perspective of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) leading the albinism issue – is and has always been the funding problem. The way funding comes in for NGOs serving people with albinism is unpredictable. When programs end, NGOs and activists working in this space have to lobby or repeatedly advocate to protect past funding or to prevent their budget from being cut by a new officer at the funder level who knows little to nothing about the issue of PWA. Going through this cycle, again and again, is exhausting. For example, I also lead the Albinism Society of Kenya. We are 16 years old, yet we are starting over and over again in terms of finding money to operate. How do we stabilize organizations of people with albinism so they can stand on their own? To do this, we need to be able to retain and hire reliable and capable staff. Current funding levels for NGOs like ours need to be higher to attract and retain qualified personnel. So, our NGOs are often used as a steppingstone by various interns and career beginners. We don’t mind training fresh graduates who are PWA. We don’t mind providing internship programs but not for all staff positions. To bridge this gap, I have often had to spend my own money, and I know that I am not unique in this respect among other NGOs working on albinism.

Some way to overcome this issue is multi-year funding. Funders can have a new vision of giving for three-years at a time; this could help our planning processes. Meanwhile, we NGO leaders need to think strategically. We could aim to source funding to purchase property/housing where we can work and rent out space as a source of income.

The second barrier – and I should say that this is also an opportunity – is for PWA leaders to work at a re-issuing a new narrative about us. It was right to have spent the last decade and half speaking about our issues such as the violence and attacks targeting PWA, but now we also have success stories. Let’s re-write our history with this, without erasing the reality that some cases of attacks continue; we need to intersperse those heinous cases with the uplifting ones. Both are awareness-raising in their own ways. Finally, we should also highlight how emerging issues impact PWA. We saw how PWA were affected in particular ways by the COVID-19 pandemic. How some of us were isolated or mistreated on the misbelief that we were natural carriers of the virus because we are “white.” PWA are also impacted by climate change given our vulnerability to skin cancer from harmful sun rays. I am seeing a trickle-in of albinism in climate change discussions, but this can be improved.

I end with a clarion call to PWA at various levels.

Seek first the political kingdom, and everything else can be added to you.

Politics remains a powerful tool of inclusion for people who have been historically marginalized. For those who are willing and able, here is my advice to you – for what it’s worth – go for it but be prepared to be resilient, to withstand discouragement and to overcome them. Work hard. For a PWA, you must try ten to fifteen times harder than others. However, this can also be used against you because, in the competitiveness of politics, your commitment may be misunderstood or even misinterpreted as a threat. They wonder what you can be if you do so much despite your physical challenges. The irony is that once a PWA becomes a successful person, you become a major competitor. You may be seen as shining too much, and you may be eclipsed. Your achievements may be understated. Your shortcomings and failures may be (over)amplified, and your realistic gains may not be recognized. You may be treated unfairly, or your achievements belittled or tied only to your disability. Even in the mainstream of the mainstream, discrimination may persist in this regard.

To all PWA leaders, I would say: build from the gains of the disability movement and its discourse. We did not stand alone in Kenya, and this was our triumph. In addition, activism with visionary leadership is important. It is not enough to know how to design beautiful reports; you must have or work with someone who has strategic vision. In my case, I worked with Alex Munyere, a PWA from the National Council for Persons with Disabilities. Together, Alex and I, played a critical role that cannot be overstated. We often walked in the dark, forging forward without guarantees that our dream of inclusion would be realized in each small space we occupied. But we kept groping in the dark, doing our part very well. We kept going. We supported each other as co-leaders and allowed each other to grow. We complemented one another, and this has worked very well. I am proud to have worked with him.

Left to Right: Isaac Maigua Mwaura with Alexander P. Munyere, Senior Disabilities Services Officer, Rehabilitation and Habilitation at the National Council for Persons with Disabilities

As a trailblazer (many of us are in our countries), know that you will only achieve a few things that you wish for. But do this; lay a good groundwork for those coming after you to continue. Train as many as possible to go beyond where you have already been. The CSO (Civil Society Organizations) who moved civil rights in the US didn’t enter the white house, but they laid the groundwork for Obama, who did so about 40 years later.

To the albinism movement, let’s continue to consolidate and take up space. We need to institutionalize by being stronger at the levels we operate. Understand our complementarity and leverage that. Accept that not all will have the same level of capacity and strength. Take the narrative beyond the attacks into the area of prevention. There are many stories. Drive allies and governments from token inclusion to substantive inclusion.

I conclude with a general encouragement to everyone. Inclusion may seem like a mirage, but we must keep going. Change is slow, but it will come. In Kenya, having PWA in political spaces is normal, which is a big step ahead of where we were fifteen years ago. The election (of Martin Wanyoyi) has now emerged from my nomination. I trail blazed for Martin and no one was surprised to see his win. It was a joy to be a witness to this transformation. To see how prior work from my appointment and other work on albinism in Kenya by the government and the CSOs contributed to a more inclusive Kenya. Therefore, we should continue dreaming of a more inclusive world and a more inclusive society around us. It can take minutes to thousands of years to change peoples’ minds. But it can happen.